The Kyote #5: The Hijacking That Never Ended

The News, This Week in Japanese History, & Much More

Welcome! The Kyote trusts you slept well, because it’s Body Clock Day in Japan. That’s according to some marketing mumbo-jumbo by the healthcare arm of communications conglomerate Docomo, whose survey claims people in their 40s with children get the best sleep (!!!)

The Quiz

A picture question any Japanese person will answer instantly. Can you?

Question: what is happening in this picture?

Answer at the foot of the mail.

The Hashtags

What are Japanese netizens discussing? Top trending hashtags on Japanese X/Twitter each day this week.

Monday March 25th: #過労自殺

ENGLISH: “Suicide from overwork”

Pornographically appalling work conditions are sadly still all too common in Japan, leading to cases of workers collapsing and dying from overwork or, as in this case, taking their own lives.

The death of Yuuki Ueda (27), found unresponsive at work in Thailand in 2021, has been recognized by the Labor Standards Bureau as suicide by overwork, after his Osaka-based employer Hitachi Zosen gave an ambiguous explanation of the circumstances of his passing.

The corporate neglect involved:

Ueda being suddenly transferred to Thailand & could not return due to Covid

He was unable to speak Thai and had trouble communicating with co-workers, who were not proficient in English

Worked 100 hours of overtime/month

Was berated for mistakes on an incineration plant project for which he received zero training.

Heart-rending excerpts of Ueda’s diary were also made public by his mother today, who says, per the Mainichi Shinbun "I just want to know the truth about my son's death".

Tuesday March 26th: #松本人志

ENGLISH: “Hitoshi Matsumoto”

Movement in comedian Matsumoto’s libel case against a weekly magazine that published accusations that he forced himself on two women at a hotel party? No, not yet. Instead Matsumoto, a ubiquitous presence on Japanese TV until recently, posts a plaintive appeal on X reading, in part:

I am confused and saddened by the absurdity of my denials being drowned out and not accepted…I want to go back to comedy as soon as possible.

The post was viewed 71.5m times in less than 24 hours.

Other celebrities are also coming out in support of Matsumoto. In Japan, weekly tabloids provide crucial checks and balances as the only outlets engaged in investigative reporting, but they also have a reputation for reckless accusations in the entertainment sphere.

Wednesday March 27th: #紅麹

ENGLISH: “Red Kōji”

What's the ultimate nightmare a company can face? One of your products potentially causing deaths or sickening customers.

Kobayashi Pharmaceutical is currently facing exactly that problem with their red kōji (rice fermented with a species of mold), sold as a dietary supplement.

Two deaths and up to 109 hospitalizations for kidney damage are suspected to be linked to Kobayashi’s product, which is also sold to other companies for use in bread and alcohol items.

Amongst a bewildering array of other brands and products using the mold, notable is Kyoto-based brewer TaKaRa, who faces the prospect of recalling and destroying no less than 100,000 bottles of its Mio Premium Rose sparkling sake.

Other countries around the world are also yanking products off shelves. Worryingly, in 2014 the Japanese Cabinet Office's Food Safety Commission issued a warning regarding red kōji, citing reports of health problems amongst European consumers.

Thursday March 28th: #死亡確認

ENGLISH: “Death Confirmation”

Anatomy of a urban legend:

Gosho Aoyama, creator of manga franchise Detective Conan (“Case Closed” in English), visits Universal Studios Japan — this trends on X.

Someone dies of a brain hemorrhage — this trends on X.

Somebody sees the trends and asks if Gosho Aoyama died.

Thousands of people retweet it.

“Gosho Aoyama died of a brain hemorrhage” trends.

He’s fine.

Many commenters compare X’s trending algorithm to Pythagoraswitch, a children’s TV show which is the equivalent Japanese colloquialism of a Rube Goldberg machine.

Friday March 29th: #国歌斉唱

ENGLISH: “National Anthem”

Why, it must be another furious controversy about that traditional cultural flashpoint: the obligation to sing Japan’s national anthem at public school graduations. Err, no.

This time the National Anthem is trending because boyband Be:First, formed via reality show in 2021, belted it out at Tokyo Dome before tonight’s Yomiuri Giants-Hanshin Tigers baseball game.

Reviews run the range from miraculous through amazing to sublime.

Saturday March 30th: #死ねない理由をそこに映し出せ

ENGLISH: “Share Your Reasons Not to Die”

A call goes out for J netizens to share pictures of things so dear to them they make life worthwhile.

Anecdotally, then, Japanese people seem to be living for a mixture of: their favorite anime, plastic models, pets, their favorite band member, or the fact that in Buddhism children who die before their parents go to hell (don’t worry, Buddhist hell isn’t eternal — it only lasts 339,738,624×1010 years!).

Today, Sunday March 31st: #ルメール骨折

ENGLISH: “Lemaire Injury”

Horse racing is extraordinarily popular with a large swath of middle aged Japanese males. French jockey Christophe Lemaire took a brutal tumble during a race, which required the horse he was riding to be destroyed. Apparently this will mess up commenters’ foolproof betting systems with which they were guaranteed to get rich (!) There’s a life lesson there somewhere…

The Word

A vast array of foreign words have been gobbled up into the Japanese language, usually without chewing. This is the “Lost in Translation” effect. Here’s this week’s word:

U is for uchi geba

What it should have been: “infighting”

Uchi is Japanese for internal, while geba is short for Gewalt, i.e. the German word for violence. Uchi geba is a mish-mash coined in Japan referring to the vicious internal feuds amongst factions of the left during the 1960s and 1970s, which sometimes resulted in mass murder.

Usage:

最近、ラディカルな左翼のグループ内で内ゲバが激化しています。

“Recently, uchi geba has intensified within radical leftist groups."

The History

This week in Japanese history the following event occurred…

The Hijacking That Never Ended

Women and children released at Fukuoka airport. Image: Mainichi Shinbun

Fukuoka is a city on the southern island of Kyushu, 880km (550 miles) from Tokyo.

Cuba is a country in the Caribbean, 12000km (7500 miles) from Tokyo.

A Boeing 727 aircraft had, in 1970, an operational range of about 4500km (2500 miles).

The first demand made by the hijackers of the Yodogo, AKA Japan Air Lines Flight 351, airborne on a domestic flight from Tokyo to Fukuoka, was for the pilots to fly, non-stop, to Havana.

This was only one of a litany of extravagantly poor decisions made by a gang of college students who, more than 50 years after the hijacking, remain trapped in bizarre exile in North Korea.

The story has three parts:

I. Monty Python’s Flying Hijack

II. The Wife-Snatching Program

III. Limbo, North Korean-Style

* * *

ACT I: MONTY PYTHON’S FLYING HIJACK

The 1960s have come to a close, and puzzlingly your small far-far-left faction of the Communist League based in Japan has not yet managed to bring about the fall of the racist, imperialist United States, currently sternum-deep in the whole Vietnam War imbroglio.

What can one do in such circumstances except commit terrorist outrages?

Mastermind is the wrong word to describe Takaya Shiomi, the college dropout who led the Red Army Faction. Expelled from the Japanese Communist Party together with his group for advocating immediate armed revolution, he tried his best with what he had, lobbing a couple of molotov cocktails at 3 police boxes then scarpering, which became in the faction’s internal lore “The Osaka War”.

For their next trick these youngsters decided on an airplane hijack, the political value of which had been demonstrated two years earlier with the 1968 hijacking of El Al Flight 426 by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. In that case, both the hijackers and the hostages went safely free — and a point had been made on an international scale.

Thus Shiomi assembled his team, with himself in the lead, missives to the authorities written and ready, and set off on the mission…

…which had to be quickly aborted — air travel still being rare at the time, especially domestically, the crack team of terrorists thought they could board a plane with train tickets.

But that wasn’t going to stop them. Nor were they deterred when hapless leader Shiomi was detained by the Tokyo police in what seems to have been a completely coincidental case of mistaken identity.

The hijackers pushed on though, and, on March 31st 1970, somewhere over Mt Fuji Takamaro Tamiya stood up, whipped out a katana sword, shouted “We are Ashita no Joe!” (the name of a comic book about a bantamweight boxer triumphing over the odds) and took control of the plane.

The hijackers, nine in all including a 16 year old boy, got a rather rude surprise when the pilot told them an unscheduled trip to Cuba would involve shunting the plane into the Pacific and a lot of swimming, so they ad-libbed a new demand to reach the nearest left-wing country they could name, that being North Korea.

After releasing women and children in Fukuoka, the Yodogo’s original destination, they set off for the socialist paradise — but the authorities had a different idea. Instead the pilots were directed to Gimpo airport in Seoul, which, like some enormous movie set, was hurriedly being dressed to resemble Pyongyang.

This apparently involved rapidly procuring North Korea flags plus hiding western aircraft behind some hangers, although the airport authorities couldn’t do what was needed to mirror actual Pyongyang, which was to reduce the surroundings to a carnaged agrarian economy.

They also put some chucklehead in charge who, as the Yodogo came to a halt on the asphalt, had the bright idea of getting on a microphone to announce “Welcome to Pyongyang!” which even the credulous hijackers thought was suspicious.

Eventually, three days later, the remaining passengers were released in return for a single hostage: Japan's Vice Minister for Transport, Shinjiro Yamamura, one of those quietly heroic personalities that bureaucracies usually screen out before they reach a position of responsibility.

On April 3rd, the Yodogo made it to North Korea, and we have a wonderful photo of the hijackers handing in their weapons — unable to decide which to use between Japanese sword, pistol or bomb, they were dripping in all three, testament to this era’s disregard for air transport security.

“You want some weapon?” Image: Mainichi Shinbun

And they reason they wanted to go to Cuba in the first place? A quick sojourn with Castro to “continue their revolutionary training”, which meant the usual left-wing radical wet-dream curriculum: how organize a movement into secret, compartmentalized cells; bomb-making; agitprop; counter-surveillance; knife fighting; smoking cigarettes while sunglassed; picking up chicks (what they should’ve done, of course, was what revolutionaries everywhere did that decade, which is watch and re-watch Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers and take notes). Six months or so would do it, then they’d somehow make it back to Japan, possibly in fake moustaches, to continue the revolution.

What we have here, then, is a group of youngsters obsessed with aesthetics of revolution, and as such, intellectually, they should have gone off to, say, the Left Bank in Paris, or the Chile of Allende. Anywhere, in fact, other than the ascetic, hungry, fanatical North Korea.

Into whose maw they now fell and disappeared for years.

* * *

ACT II: THE WIFE-SNATCHING PROGRAM

According to the hijackers’ own narrative, the first five years after the hijacking were spend “completing studies”, which sounds ominous if you’re familiar with North Korea.

We can’t know for sure but it seems likely that, in the manner of all paranoiac regimes, Pyongyang wanted to assure themselves that the hijackers were not, in fact, part of some convoluted CIA scheme to infiltrate the country. In other words, the Yodogo gang quickly found out that they would not be allowed to leave, for Cuba or anywhere else.

Eventually, the hijackers’ situation stabilised, and they were set up in a little compound, decently treated by western standards and extravagantly privileged by Pyongyang’s, where they were encouraged to opine about world events, a sort-of propaganda unit with channels of communication to their left-wing peers in Japan.

Through those contacts, the hijackers started to let it be known that they would, in fact, very much like to return to Japan — and perhaps they could’ve done, served a sentence then moved on (like their hapless leader Shiomi, arrested after the hijacking and sentenced to 20 years in a Japanese prison, something he later described as a blessing in disguise) — but instead, they became involved in a series of bizarre events that has prolonged their exile to this day.

* * *

One of the Yogodo gang, Shiro Akagi, had a Japanese girlfriend who agreed to travel to the compound and live there — which must’ve been very nice for him.

Not so nice for the others — all male — and it’s not difficult to imagine that they decided they rather liked the idea of having relationships too.

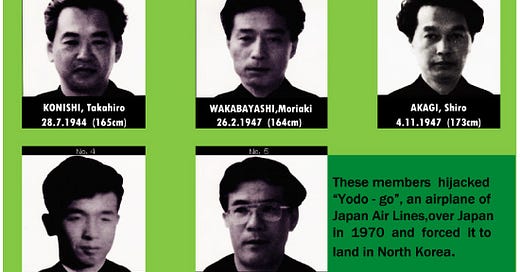

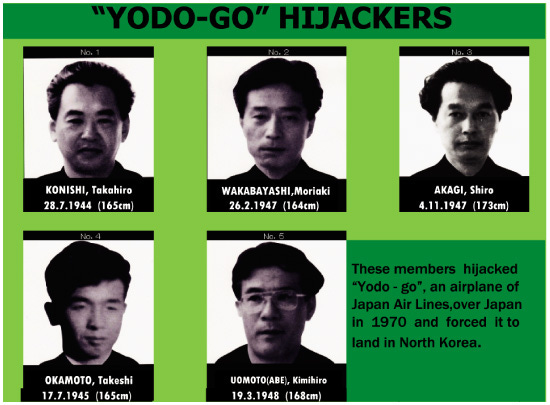

Image: National Police Agency

What happened next is in dispute. The hijackers have always insisted they did not, with the North Korean authorities, set up an international people-snatching operation to provide themselves with women.

Their opponents say that’s exactly what they did — in one case enticing a left-wing activist to fly over from Japan to visit their compound then refusing to let her go.

There is also evidence that they trolled Europe for vulnerable Japanese students studying overseas. In one case a family received a postcard from their daughter explaining she had finished her course and was going to travel for a while. In the era of snail mail rather than international phone calls or messages, the family was none the wiser as to their daughter’s fate until they learned was in North Korea and married to one of the Yodogo group.

What we know for sure is this: suddenly the hijackers were telling their contacts not only that they had married, but that they wanted to secure Japanese citizenship for their children — who, having been born in secret, were officially stateless.

This naturally set off alarms, as the Japanese government rushed to find out whether any of their female citizens had been hustled off to the North against their will to marry the hijackers. By moving through third countries (or, critics insist, being moved through third countries) the wives had managed to evade notice, and come in and out of Japan repeatedly.

The resulting firestorm (eventually the wives were arrested and charged with passport violations) meant the prospect of the hijackers returning home was postponed indefinitely. Later, all of the children decided to leave the compound and go to Japan, a country they had never known except in stories their parents told.

The Yodogo gang for their part have always insisted the marriages were kosher, and in fact the remaining members — happy, they say, to face justice for the initial hijacking — still to this day refuse to return to Japan while they face charges related to their families.

The closest they came to conceding anything untoward was in a book of interviews with Takamaro Tamiya, published posthumously after the hijack leader passed away in North Korea in 1995, where he states “finding women was a revolutionary task”, and that the wives were to be used explicitly to pass freely in and out of Japan without the authorities noticing — which is at best an unromantic view of marriage.

* * *

There is also the bizarre saga of the “super K” banknotes. In the year 2000 the CIA, investigating the passing of very high quality fake $100 bills, tracked them to a casino in Thailand. The Thai authorities in turn found a small, mysterious trading company run by an Asian man from where the false bills seem to originate.

When the authorities moved in, the man was picked up in a car by two North Korean diplomats who rushed him over the border into Cambodia. After a 2 day stand-off all three were arrested, and invoked diplomatic immunity. The mysterious Asian man turned out to be none other than Yoshimi Tanaka, one of the Yogodo hijackers.

Tanaka was extradited back to Thailand, where he was acquitted of forgery before accepting a return to Japan; put in prison for the Yodogo affair he died in 2007 of liver cancer before he could be released.

With the banknotes affair hitting the global headlines and raising the possibility that the hijackers were continuing their international criminal careers, the hope of getting back to Japan was again thwarted.

ACT III: LIMBO, NORTH KOREAN-STYLE

The 4 remaining hijackers, plus 2 wives, at their compound in North Korea. Image: their own website (http://www.yodogo-nihonjinmura.com/). Caption: “Welcome to the Yodogo Japanese Village”.

Over the decades the Yodogo hijackers kept up a flurry of periodicals to try to influence public opinion in Japan, so it may not come as a surprise to learn that they have put the Internet to use for the same purposes.

Which is why they are probably the only non-governmental group in North Korea with a) a homepage, and b) a Twitter account.

Reading the content on these two mediums gives a fascinating picture of a group still wedded to their left-wing ideology (with satellite access to Japanese TV they claim to see signs of an upcoming revolution everywhere), who also have to bat away trolls who, say, share pictures of luxurious-looking sushi, taunting them about the diet in North Korea.

They also address earnest queries from ordinary Japanese asking if they regret the hijacking that led to the 50-year long-and-counting limbo existence.

To their credit, the group now admit the crime was the result of youthful folly, with one, Moriaki Wakabayashi even recalling with regret how he refused to let a hostage leave the airplane when women and children were released, despite the man pleading for the chance to see his dying parent one last time.

* * *

On August 29th 2018, the Yodogo hijackers’ Japanese supporters posted the following on Twitter:

「我々としては、一定の役割を果たしたと考えており、(中略)やめても構わないと思っています」とのことで、Twitter投稿その他を終了とさせていただきます。今まで、ありがとうございました 事務局より

“We feel that we have fulfilled our purpose…[abridged]…and it will cause no harm for us to stop”…therefore we will cease posting on Twitter and other forums. Thank you very much for your support.”

With this enigmatic sign-off, contact between the last 6 members of the Yodogo Japanese Village and the outside world ceased.

Hijackers Roll Call

The Remaining Four

Takahiro Konishi – Still in North Korea

Shiro Akagi – Still in North Korea [first hijacker to have wife & children]

Moriaki Wakabayashi – Still in North Korea

Kimihiro Uomoto – Still in North Korea

Made it Back to Japan

Yasuhiro, Shibata – Arrested in Japan in 1988 after traveling to Japan on a false passport. Sentenced to 5 years in jail.

Yoshimi Tanaka – Arrested in Cambodia in 2000 for the Super K banknotes affair. Died in 2007 of liver cancer while serving a 12-year jail sentence in Japan.

Lost Earlier

Takamaro Tamiya – Died in 1995 [illness]

Yoshida Kintaro – Died in 1985 [acute liver atrophy]

Takeshi Okamoto – Believed killed trying to flee North Korea with his wife

With thanks to William Andrews, author of The Japanese Red Army: A Short History.

More at Wikipedia.

More at William Andrews’ site Throw Out Your Books.

The Film

Each week The Kyote introduces a movie which was retitled for the Japanese market.

Film: NON-STOP (2014)

Japanese title: フライト・ゲーム

Literal Translation: “Flight Game”

2014’s entry in the Liam Neeson geriatric wish fulfillment genre, depicting an air marshal — haunted by the death of his wife! — forced to perform various tasks by hijackers lest the flight be brought down. The “following the hijacker’s instructions” aspect got the “Game” part added to the title in Japanese. An example of Movie Retitled Case #11: Changing Title to Evoke Genre Trope(s) in Target Language.

The Answer

Question: what is happening in this picture?

Answer: she is announcing a court verdict (“guilty”)

After high profile court proceedings, supporters usually unfurl a banner announcing the verdict to the waiting press. In this case the banner, known as a "senninbari" (千人針), reads 有罪 (guilty) — presumably the woman in the picture is supporting the defendant(s), because she doesn’t look too thrilled.

Until next week,

The Kyote

New? Sign Up Here

Feedback? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote published every Sunday from Kyoto, Japan