⛩️ #39 Did This Man Get Away With Two Murders?

The still-unsolved deaths of two Japanese women in L.A.

It’s midday, November 18th, 1981.

Clothing importer Kazuyoshi Miura is on one of his monthly Los Angeles trips, checking out the latest American fashions and buying up stock to sell back in Tokyo.

This time he’s brought his wife, Kazumi, with him.

They’re driving through Downtown, passing Little Tokyo, LAPD HQ, City Hall, the Civic Center.

A couple blocks north, they stop the car to snap some pics in the shadow of the LA’s famous stacked interchange, the four-level symphony of concrete, chaos and honking horns that symbolises post-war America’s obsession with cars.

Below the traffic, in a side-street, Kazumi stands in the middle of the road, takes off her sunglasses, fluffs her hair and squints at her husband. Kazuyoshi clicks frame number one, grins and smiles and winds the film, brings the camera up to his eye again and —

Seen through the viewfinder — BANG! — Kazumi’s head explodes.

Kazuyoshi dumbfounded, not a clue what just happened. Drops the camera. Runs to Kazumi, now a lump on the asphalt. He doesn’t hear the other BANG — but later he’ll realize he felt a sudden searing pain in his leg.

He’s kneeling by Kazumi now, trying to understand why blood, skull and brain matter is sprayed around her like a halo. She’s glassy eyed, somehow not dead, mumbling.

And now the two gunmen lope in for the spoils: one gets Kazumi’s purse, the other points the pistol and gimme-the-wallets Kazuyoshi — who fumbles his billfold to the duo before they sardine back into an old green sedan and rev off into the distance.

Kazuyoshi’s back to Kazumi — Kazumi? Kazumi? Her jaw making the same movement over and over like factory machinery, trying to speak. He puts an ear to her mouth but it’s nonsense, random syllables and hiccups and in the distance the sound of sirens.

Under the palm trees and blue skies, LA is a city of devils.

Crime in LA has always held a dark allure, reminding us that, in contrast to the paradise the tourism department promises, Tinseltown can be the place where dreams get carved up and gutter out.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were boom time for LA bloodbath artists: the Hillside Stranglers killed ten women and girls, The Freeway Killer 14 men and boys, Doug Clark and Carol Bundy exercised their penchant for necrophilia and decapitation along the Sunset Strip, while a never-ID’d nutbag butchered ten homeless on Skid Row and legendary porn swordsman John Holmes got caught up in the quadruple Wonderland Murders — which also remained unsolved.

LA had gained the reputation of one of the most floridly dangerous locales on Earth, and now marauding urban youths had casually gunned down a Japanese couple for the contents of the husband’s wallet.

By the way: Kazumi had survived the headshot — for now.

The ambulance got her, a plastic bag full of brains, plus Kazuyoshi, who’d taken a bullet to the thigh, to the ER where Kazumi was quickly hooked up to a ventilator.

Kazuyoshi’s wound was treated while he told two detectives from Central Robbery what had happened — a conversation which was probably the quietest one for the rest of his life.

Because within hours it was a media zoo. Local press picked up the story, followed quickly by the national outlets — and soon Tokyo telexes were chattering to life and Japanese reporters had booked out every flight from Narita to the west coast.

Overnight Kazuyoshi finished the official police interviews, then started talking to the press. With a local Japanese friend acting as interpreter, Kazuyoshi raged from his hospital bed against the mean streets of Los Angeles, telling reporters that he’d be writing then-President Ronald Reagan, “to protest this incident and ask proper care and protection against this sort of incident happening again.”

Across the ocean, the Japanese public were having their worst fears about American street violence confirmed. Expecting Japanese-style damage control mode — supplicating apologies and hand-wringing — they instead got the American version: that is, civic boosters with one eye on the forthcoming LA Olympics downplaying the incident and insisting the city was, in fact, safe, despite this latest “anomaly”.

Amid the fallout, Kazumi Miura clung to life: blind, paralyzed, unconscious and dependent on a life support machine. Kazuyoshi, instantly becoming a media fixture known as the “tragic husband”, demanded her repatriation be paid for by the American authorities, who flew her back to Japan on a military aircraft — whereupon he performed a daring act of heroism, using signal flares to guide the helicopter carrying Kazumi to the rooftop of a Tokyo hospital.

Then, almost a year to the day after the shooting, Kazumi Miura passed away in a Tokyo hospital, making the case officially murder.

But here’s the thing: the two Central Robbery cops who had initially caught the case thought Kazuyoshi was bullshit.

He had the shooters as Latinos, escaping in a green sedan. A couple of witnesses at a nearby Department of Water and Power building overlooking the scene swore the attackers were in and out of a white van — and maybe not Latino at all.

Plus Kazuyoshi had a record — for arson. Sure it was distant past, but he had served a few years in juvie prison. Also: the guy was a playboy. He liked money and he liked girls. A lot.

The Central Robbery detectives didn’t like his attitude either — more grandstanding media attention-seeker than confused and grieving husband.

But what they thought didn’t matter, because the trans-Pacific outrage quickly took the case out of their hands — it was given to the Major Crimes Unit, who came to the quick conclusion that Miura was kosher and they were looking for a couple of deranged Latino hippies.

Then, as Kazuyoshi Miura remained one of the most photographed men in Japan, the trail of Kazumi’s murder went cold — and it would’ve stayed that way forever if it wasn’t for a tabloid magazine, and one very persistent Japanese-American cop.

THE COP

Jimmy Sakoda is third generation Japanese, born to farmers in Seattle in 1936. Five years later, Pearl Harbor happened and Jimmy plus family were rounded up and imprisoned in the Tulelake internment camp.

Young Jimmy, who had been growing up quite the all-American, suddenly found himself being schooled in Japanese, a language he didn’t know, plus kendo, judo and spartan samurai-esque educational methods like being forced to stand holding two buckets of water whenever he goofed off.

Jimmy embraced the discipline, learned the value of persistence, and walked out of the camp a serious young man who did not let rejections — like a Catholic school refusing to even discuss admission of a Japanese-American — stop him from making it to UCLA, followed by a stint in the Army that had imprisoned him and 120,000 other Japanese-Americans for the duration of the war.

Afterwards he joined LAPD — then basically a paramilitary force of headbreaking Irishmen — and was elected president of his class at the police academy.

As one of the few non-white officers, Sakoda was relegated to working in predominantly minority areas — including a stint in narcotics, undercover as an evil Asian drug dealer.

However, by 1975 Southern California was attracting thousands of Asian immigrants thanks to a liberalized immigration law a decade earlier, and Sakoda saw the chance to build bridges with these new communities — by recruiting officers like him, familiar with Asian languages and culture, to populate a new command. He founded what became known as the Asian Crimes Squad, and in 1976 became the first Japanese American lieutenant in LAPD history — swiftly followed by 1977’s award for Best Police Officer in the United States.

On the day of the Miura shooting, Lt. Sakoda was in Tokyo attending a U.S.-Japan crime conference. As the first reports were shared in the hotel hallways, he had no idea he would end up pursuing the case for the next 27 years, through a labyrinth of twists and turns that would take him from the Downtown LA crime scene to a tropical paradise, to receiving one of the highest honors the Emperor of Japan can confer — and to the shocking conclusion of the investigation.

BULLET OF SUSPICION

1984. Three years post-shooting; 2 years since Kazumi Miura lost her fight for life in a Tokyo hospital having never woken from her injuries.

Kazuyoshi Miura seems to have gotten over the whole dead wife thing — he’s married again, and has set his new bride up with a fashion store named after his clothing import biz plus her name: Fulham Road Yoshié becomes the happening place to go for groovy foreign outfits plus the chance to meet the famous playboy with the tragic past.

Lt. Jimmy Sakoda has been monitoring the halfhearted ongoing investigation by LAPD Major Crimes Unit — still wedded to the random homicidal hippies theory — with such persistence he’s been told to back off. Miffed Major Crimes detectives even start spreading rumors Sakoda has a personal backdoor to the Japanese press and is leaking information to them.

The accusation is the final straw: a disgusted Sakoda decides to retire from LAPD after 26 years of service.

Then a bolt from the blue in Tokyo: weekly tabloid mag Shukan Bunshun begins a series of articles entitled Bullet of Suspicion (疑惑の銃弾), accusing Miura of staging the shooting to collect a fat life insurance policy he had taken out on Kazumi.

Kazuyoshi Miura is instantly re-besieged by the media, again the most famous man in Japan — and in the frenzy of attention several important readers pour over the Shukan Bunshun revelations.

The First Victim?

One reader in particular wept as she went through the pages of Bullet of Suspicion. She had a sister, named Chizuko Shiraishi, who had been missing since 1979. Chizuko had been romantically involved with Kazuyoshi Miura and had flown alone to Los Angeles in March 1979 without telling her family the reason she was going.

Chizuko Shiraishi had never been seen again.

Now officially missing for five years, the articles convinced her family that erstwhile boyfriend Miura had something to do with her disappearance — in the same city where his wife had been shot 2 years later.

Had Kazumi been the second woman he had killed in Los Angeles?

Chizuko’s family sent her dental records to LAPD and prayed.

Here’s what had happened to Chizuko:

On May 4, 1979, a little over one month after she arrived in Los Angeles on PamAm flight 002 from Tokyo, a young boy discovered the skeletal remains of an unidentified woman in a vacant field in the hills north of LA.

The location was remote enough to ensure the body would not be found for some time. LAPD Foothill Area Homicide Unit handled the initial investigation, but the body was in an advanced state of decomposition and neither a cause of death nor identity could be ascertained.

Until Chizuko Shiraishi’s dental records arrived — and revealed it was her.

Investigators on both sides of the Pacific woke up to a possible first murder, and looked into Miura’s 1979 movements:

Two days prior to Chizuko’s arrival in LA, Miura arrived on a flight from Tokyo — and left a week afterwards, alone. He had been in town when she disappeared.

Chizuko had traveled to LA having no other reasonable purpose other than to meet Miura, her boyfriend. However, Miura later made statements denying he ever saw her there.

Upon returning to Tokyo, Miura began a two-month process of liquidating Chizoku’s bank account of approximately $20,000.

Miura also made false and inconsistent statements to people about Chizoku’s whereabouts, telling them she was visiting family, caring for her sick mother or that she had moved to Hokkaido and was living with someone else.

Miura was also seen removing Chizoku’s personal belongings from their shared apartment, including items of clothing and cosmetics, much of it unopened. He discarded these belongings in the apartment complex trash bins where later an apartment manager who had witnessed Miura’s actions retrieving many of the items for his own wife.

Soon afterwards, the same manager noticed a young woman he had never seen before entering the building — it was Kazumi, introduced as Miura’s new girlfriend. Miura explained they were getting married and they were moving out because the apartment was too small for them.

So: 1979. Chizoku lay dead on a remote LA hillside. Miura emptied her bank accounts and replaced her with Kazumi. Two years later Kazumi takes a bullet in the head in the same city.

All circumstantial evidence to be sure, but investigators — including Jimmy Sakoda — became convinced Kazumi was actually Miura’s second victim.

The cops kept quietly working the case, while, in Tokyo, things were getting surreal.

The Porn Star Attempted Murder

After the Shukan Bunshun revelations, Miura figured he was the subject of about 25,000 newspaper stories, and “was featured on about 15 different TV programs a day. One of them even detailed my dinner menu, which they guessed from items I shopped for earlier in the day.”

Not exactly the shy and retiring type, he cashed in by publishing an autobiography, Opaque Time, and gave interviews to all and sundry promoting his wife’s fashion boutique.

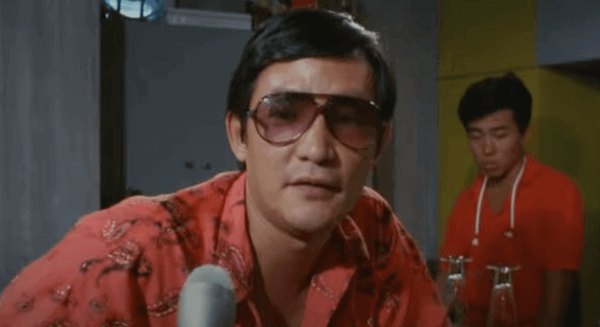

The height of the media absurdity around the case was 1986 movie No More Comics! which details the struggles of an entertainment reporter and satirizes media manipulation, doing so by incorporating real-life incidents from around the time of its late 1985 filming — including the Miura case.

The reporter is singer-actor Yuya Uchida — who also played real-life killer Kyoto cop Masaharu Hirota in The Mosquito in the 11th Floor (covered in The Kyote #28 here), and also subsequently was himself accused of violence against a woman — and amongst the ways the movie plays with its meta-narrative includes having the reporter grabbing an impromptu interview with the real-life Kazuyoshi Miura.

You can watch the scene on Youtube: Miura berates Uchida for invading his privacy, douses him with Coke then physically ejects him from the bar where the interview is taking place.

If the hospital bed insistence on writing to Ronald Reagan didn’t tip you off, or the rooftop stunt with helicopter signal flares, then his decision to appear as himself in a movie to berate the press for their interest in him should make it clear we’re dealing with a genius of narcissism.

Then the porn star came back into Miura’s life.

This was yet another woman in Miura’s life, a wannabe actress whose only screen appearance had been fifth banana in a softcore flick. According to the woman, anonymized as “A” in the mainstream Japanese press, she first met Miura when he chatted her up at a coffee shop in Shibuya in mid-June 1981.

Getting handsy with each other over the next few months, Miura engaged full-on manipulation mode, telling the vulnerable young woman struggling to survive Tokyo how much he believed in her acting skills, oh, and he’d also like to marry her. There was just one impediment to the nuptials: his wife Kazumi.

Nothing that a quick murder couldn’t solve.

“A” agreed to kill her.

And it was going to happen in Los Angeles.

It turns out that, months before Kazumi was shot in the head, she had survived a first attempt to murder her.

“A” testified how it went down:

Over coffee in Shibuya, Miura suggested a trip to Los Angeles where “A” would shoot Kazumi in the head with a pistol and himself in the leg to make it look like a legit crime, but “A” refused, not knowing the first thing about guns.

Knifework was Miura’s second suggestion, but “A” was rather concerned about blood splatter (whether for evidentiary reasons or to avoid ruining a nice outfit is not recorded). Eventually the compromise of an iron block smashed on the back of Kazumi’s head was agreed upon.

Miura arranged for himself, Kazumi and “A” to stay at the same hotel during his next visit to Los Angeles. On the evening of August 13th — two months before the LA trip where Kazumi was shot — Miura came to “A”'s room in the hotel just before the crime to hand over the iron block in a bag and instruct her to “wipe off any fingerprints after the crime.”

“A” proceeded to Kazumi's room, pretending to be a Chinese seamstress who had come to take her measurements for clothes, despite not bringing any sewing tools with her. Once inside, “A” played mute, and wordlessly gestured to Kazumi as if about to take her measurements. As Kazumi turned around, “A” took out the iron tool and smashed her in the back of the head.

It didn’t go as planned.

Kazumi turned around, grappled “A” to the floor and held her down, “A” instinctively breaking character by saying “I’m sorry” in Japanese (ごめんなさい).

“A” fought Kazumi off, and escaped.

We don’t know what the hell Kazumi thought had happened, but we do know she didn’t call the police. Probably Miura talked her out of it. We only have “A”’s word on what happened in the room and it took her 4 years to come forward, so no doubt she told and re-told herself the story until she arrived at a version that put her in a decent light — she was an actress after all.

We do know Kazumi went to two different doctors to have stitches put in her head, then removed — this became very significant as to just how bad her wound was and if it was an attempt to kill or just injure her.

Now, with “A” coming forward, the cops suddenly had a case against Miura with a living witness. For now, they put the deaths aside — thinking they had him on a plate for this earlier attempted murder of Kazumi.

Jimmy Sakoda’s Act II

Jimmy Sakoda had retired from LAPD, disgusted at the rumors that he was leaking Miura information to the Japanese press.

But he was a born lawman.

Screw the Major Crimes people if they weren’t taking Kazumi’s death seriously, and didn’t care about “A”’s new revelations — Sakoda gathered all the private data he had amassed and appealed directly to the Chief Attorney of the Los Angeles District Attorney's Office.

They appointed him an investigator in the DA's office, and ordered him to led the first ever joint Japan-US investigation with Masahiro Terao, then Chief Investigator of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department's First Investigation Division.

It was time to put Kazuyoshi Miura in cuffs.

The Trial for Attempted Murder

September 11th, 1985, just after 11:20pm, Miura had just finished yet another TV interview at the Ginza Tokyu Hotel when the cops grabbed him up.

“A” had been arrested the same night.

Miura denied everything. At first. Then, with narcissistic glee, he slowly drip-fed information to the outside world.

Yes, he knew “A” — he’d been banging her. Yes, he’d given her money — but not to whack Kazumi, instead for an abortion.

No, he hadn’t seen “A” in LA, even though the three of them stayed in the same hotel — it must have been a colossal coincidence.

As he sat in pre-trial detention, Miura also dug into the narcissist’s trial delay playbook: demanding a different cell due to back pain, going on hunger strike (he lasted a day and a half before relenting).

Then, pouring over legal tomes in his cell, he came up with a successful procedural maneuver: gathering a group of prominent lawyers to argue a fair trial was impossible because of media attention, then suddenly firing the lot of them, thus gaining a five month delay as his new lawyers got up to speed.

Meanwhile “A”, who was tried separately, got 2 and a half years in prison for smashing Kazumi on the skull with an iron block, arguing successfully that she “lost her murderous intent” after the first blow — which is a little late if you ask us.

Eventually, after exhausting every delaying tactic he could, on 7th August 1987, the verdict on Miura came in. In the count of attempted murder of his wife Kazumi in an LA hotel in concert with “A”:

Verdict: guilty

Sentence: 6 years imprisonment.

Kazuyoshi Miura was finally in for an extended prison sojourn.

Slow & Steady

Miura may have been behind bars, but the cops didn’t give up their attempts to prove he was responsible for Kazumi’s death.

Their methodical work resulted in breakthroughs:

Before the “A”/iron bar attempted murder, Miura had tried to entice an LA-based Japanese sushi chef to kill Kazumi.

At a motel where Miura usually stayed in Los Angeles, the sushi man listened to Miura's philosophy of the perfect crime for about three hours — then turned down the chance to do Miura’s dirty work.

Remember the camera Miura was holding when Kazumi was shot? The photos were belatedly scrutinized — and showed that Miura had visited the crime scene earlier in the day.

A witness also saw a man fitting his description making a call from a public phone in the area around this time. Police speculated this earlier visit was a trial run Miura took alone earlier in the day before the actual shooting.

Trigger Man?

In 1988, the owner of a parking lot in Toyonaka City, Osaka Prefecture, was arrested for alleged violation of the Sword and Firearms Control Law. He had smuggled a Ruger rifle back with him when he returned from living in the United States.

The Parking Lot Owner admitted possessing the rifle, having bought it from a fellow Japanese student studying at the University of Southern California. When asked why he brought it to Japan, he said that he was interested in guns and found it difficult to part with.

So what? So this: the man actually appeared earlier in this story: he was the Japanese friend who acted as interpreter for Kazuyoshi Miura’s hospital bed interviews the day Kazumi was shot.

The rifle was seized and analyzed — but it wasn’t the murder weapon.

It was also discovered the man had hired a white van in LA on the day of the shooting — remember how eyewitnesses had seen such a vehicle at the crime scene, as opposed to the green sedan Miura insisted the assailants escaped in.

Then they Got Him…Sort Of

Miura and Parking Lot Owner were charged with Kazumi’s murder.

You can imagine the bruhaha.

But they couldn’t make the charges stick on Parking Lot Man. He was found not guilty of murder due to insufficient evidence, and sentenced to 1 year and 6 months in prison for possessing the rifle.

Miura got life imprisonment for "conspiring to murder with an unknown person, based on various circumstantial evidence, including the motive."

Miura appealed to the Tokyo High Court. They thought he was lying about the green car, but, in the kind of logic unique to the Japanese legal system, because it hadn’t been proven that Parking Lot Owner was the trigger man, it could not therefore not be proven Miura had been in murder plot with him.

His appeal was granted. The prosecution appealed to the Supreme Court, but on March 5, 2003, Miura's innocence in Japan for the shooting was confirmed.

He was free again.

Jimmy Sakoda’s Act III

In 2007, Jimmy Sakoda was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, 4th Class, Gold Rays with Rosette for “his contributions to investigative activities involving Japanese nationals and to the development of investigative cooperation between Japan and the United States”.

Retired twice, from LAPD then the DA’s office, laureled by Emperor Akihito, Sakoda could have finally left the case go, but the extreme persistence he learned in a California internment camp just wouldn’t let him — and Kazuyoshi Miura’s narcissism was about to cause him to make his final mistake.

The Blog

After his release, Miura had thrown himself into the newest medium offering the oxygen of attention — the Internet. Up went a personal blog, where he promoted himself as a human-rights advocate helping people falsely accused of crimes, plus shilled his books, a DVD about the case, and tickets to gatherings featuring alleged victims of wrongful prosecution, a bargain at ¥3000 a head.

And Jimmy Sakoda, armed with another skill the prison camp had taught him, the Japanese language, was reading every word — including one blog entry where Miura mentioned international travel plans, including a possible trip to Saipan, a tropical island and popular tourist destination north of Guam.

Saipan is also a United States Commonwealth, with a similar status to Puerto Rico. Miura was coming to U.S. terrority, within the reach of the long arm of American law.

Sakoda gave the heads-up to Rick Jackson, who had worked the Miura case with him and was by then head of the LAPD’s Cold Case Homicide Unit; Jackson put wheels in motion for Immigration and Customs in Saipan to be on the lookout for Miura.

Now at this point something went wrong — perhaps some still-miffed LAPD official who remembered Sakoda’s end-around the Major Crimes Unit delayed giving the word to Saipan — and Miura got into Saipan without being stopped.

(We imagine it took all of Sakoda’s stoicism not to hit the roof when he found out)

But then, after Miura had enjoyed a nice vacation on U.S. ground, and was at the airport to return to Japan, airport officials locked him up.

Finally, on Feb 22nd 2008, 27 years after the shooting on a Downtown LA side-street, Kazuyoshi Miura was in U.S. custody.

Jimmy Sakoda visited him. Through the bars in his cell the cop looked the aging playboy up and down then uttered just one word: “gotcha”.

The problem was, while Miura was in U.S. custody, he wasn’t in LA custody.

Transferring him to the continental United States would require an official request from California (in the shape of then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger), then a series of extradition hearings. And, for a man who knew how to manipulate the law to his own ends, plus the media, there must have been some part of Miura that relished another fight.

And this was one he had a good chance of winning.

Double Jeopardy

You cannot be tried twice for the same crime — Japan, the U.S. and most state constitutions prohibit it.

Miura had been found guilty of Kazumi’s murder, then acquitted by Japan’s top court. He was innocent. It follows that Saipan authorities would have to release him.

However, in 2004 the California had passed a law allowing someone tried in another country to stand trial again in the state for the same offense — if convicted, the person receives credit for time already served in the another country, which in Miura's case would have been nearly 13 years — but it seemed possible the extradition could take place.

Miura got himself a celebrity lawyer and dug in, spending his days writing yet another self-pitying memoir, this one entitled In a Solitary Cell at Saipan Zoo. The final paragraph read “I imagine that by the time this book hits the shelves in bookstores, I will have returned to Japan and will be living the same peaceful life as before, and with a calm heart I’ll join my hands in prayer.”

After dozens of hearings, denied bail requests, appeals, re-appeals, the final verdict came back:

Kazuyoshi Miura could not be extradited on the charge of murdering his wife, due to double jeopardy.

But he could be extradited on a charge of conspiracy to murder — because Japan does not allow for the prosecution of conspiracy.

He was going back to LA to face the music.

Postscript

Kazuyoshi Miura was handed over to LAPD custody on October 10, 2008. It was his first time in Los Angeles since the shooting 27 years earlier. Hours later, he used his shirt to hang himself in his cell.

After his death, Kazumi Miura’s mother Yasuko Sasaki issued a statement: “The pain of Kazumi’s murder will never change. The feelings of the grieving and suffering family will never fade.”

After Kazuyoshi Miura’s acquittal by Japan’s Supreme Court, the murder of Kazumi Miura remains officially unsolved.

In December 2008, two months after Kazuyoshi Miura’s suicide, LAPD reclassified the “Undetermined Death” of Chizuko Shiraishi to “Homicide,” specifically “Murder.” The Department also officially named Kazuyoshi Miura as the sole suspect in her murder.

Kazuyoshi Miura, playing himself in movie No More Comics!

IMPORTANT NOTE: due to Gmail email length restrictions, we cannot include this article’s extensive footnotes in the mail-out. Please visit thekyote.substack.com to see the full footnoted version.

Enjoy The Kyote this time? Check this out next: Rogue Kyoto Cop's Killer Rampage

We’ll see each other again next week,

The Kyote

Comment? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote is published in Kyoto, Japan every Sunday at 19:00 JST

A great read, thank you!

Daniel .. thanks for the comment.

Back in the day when I was studying Japanese with an alarming intensity, my daily diet would be something like breakfast with the morning wides such as Fresh Wide or Zoom In which included Wikki-san and his one point eikaiwa lesson outside a random station with unsuspecting bleary eyed salarymen, settle down to lunch with WARATTE II TOMO (ALTA studio days) followed by the afternoon wide shows, featuring the usual suspects such as MINO MONTA and ピーコ on 3JI AIMASHO giving his rasping fashion commentaries of unsuspecting victims in a fashionable part of Tokyo... during my year on study abroad in Osaka, I was able to power up my Kansai-ben through shows such as Shoot in Saturday and DoyoDaisuki830 .. Evenings got a lot better when Kume Hiroshi pitched up in the evening with News Station which was a much higher level take (?) on the news, which would be mauled the next day in the 'wides'. .. I won't go on to 11pm, as you say probably better not to go there, although I do have a great memory of my homestay dad sliding drunk under the table during one show..

As a student going back and forwards between here and the UK it was like jumping in the proverbial shower and soaking in the endless stream of 'information' played over and over again with a slightly different take depending on the show.

Although a lot of it was trashy and spun out, it certainly provided an incredible amount of material for learning Japanese (see Krashen's input theory) It is definitely one way I learnt how to read newspapers after watching the pics on TV. Of course, we now have intravenous news feeds in multimedia, but somehow it was (don't look) .. different somehow.. いいとも!