Kazuko Fukuda whacks former co-worker Asako Takaoka. Image: ぶんか社

Dear Readers,

Japan used to have a statute of limitations on death penalty crimes like murder.

It was simple — you could stab, shoot, strangle, boot to death, poison, obliterate someone with a truck, whatever your heart desired — as long as you made it 15 years without being caught, you could waltz out of hiding, shout “you dopes, it was me!” and face zero legal consequences.

Kazuko Fukuda almost made it.

But in the end, after 5459 days of Catch Me If You Can-esque narrow escapes, she was charged with murder just eleven hours before those magic 15 years were up.

In this edition we’ll begin to tell one of the most amazing stories in the annals of crime. Let’s jump into it together…

The Murdered Hostess

19 August 1982

You’re in Matsuyama, the largest city in Ehime Prefecture, on Japan’s fourth island of Shikoku.

Kazuko Fukuda, 34, has recently quit her job at a hostess bar, where women entertain male patrons one-on-one by pouring drinks, chatting, flattering, flirting and generally creating a light-hearted atmosphere for well-healed businessmen.

She’s visiting the apartment of former co-worker Asako Takaoka, to discuss partnering up to open a “snack” (a small, casual bar which, unlike hostess clubs, are typically run by a mama-san who manages the atmosphere, serves drinks and arranges karaoke).

To say the conversation was not a success is understatement: Kazuko and Asako argue. Asako throws a wallet a Kazuko and insults her.

Kazuko lunges for a fruit knife and goes at Asako, cutting her hand.

Asako disarms her, threatens to go to the police, and forces Kazuko into a traditional Japanese dozega, the grovelling kneeled apology, head bowed until it touches the floor.

When the contrite Kazuko brings her head up again, Asako kicks her in the chest.

Kazuko loses it. Grabs an decorative cord used to secure the obi of a kimono, hoists it around Asako’s throat and in a trance of fury chokes her to death.

RING-RING

That’s the telephone, bringing Kazuko back to herself.

Shit! Asako’s dead and didn’t she say her boyfriend was going to call — before dropping by later?

Kazuko lets the phone ring out — knowing she has an hour or two to improvise a body dump.

She wedges Asako’s body into a packing case and struggles it out onto the fire escape.

Minutes later Asako’s boyfriend arrives.

Kazuko fronts him up outside the apartment door — meters away from dead Asako on the fire escape. Her story’s ready — Hi, I’m Asako’s former co-worker. She told me to tell you to meet her at Karakohama, a beach on the other side of Ehime.

Yes: tonight, now — better get going. Why? Sorry, not a clue.

It’s 1982, pre-cellphone. The confused boyfriend heads off — and now Kazuko has another ticking clock: the beach is an hour’s ride away. Figure boyfriend sticks around an hour or two waiting for Asako to appear, then comes back here.

Three-four hours to get the next step done. Here’s the idea: if Asako vanishes and so does the contents of her apartment, people will think she’s done an overnight escape act to leave her problems behind — something so prevalent in Japan there’s a word for it: 夜逃げ (yonigé), literally “night escape”.

Kazuko calls her second husband Nobuo: “I’ve got a friend with a violent husband, he’s getting out of prison, she’s decided to yonigé away from him. We need your help. Yes, now.”

Nobuo arrives at the apartment. “Where’s this friend then?”

His wife answers, “I killed her.”

Now that’s what we call a bit of a facer.

Nobuo remonstrates, tries to get Kazuko to go to the police — knowing the low chance his headstrong wife will listen.

Ten minutes later, Nobuo finds himself manhandling the packing case with its human cargo down the fire escape…

…and when he gets it to the family minivan, Kazuko realizes her husband has brought one of their four kids with him— their 5-year-old son.

The kid’s on the back seat sucking his thumb as his parents manoeuver the packing case in beside him.

Nobuo drives away, leaving Kazuko to work the next phase — disappearing the contents of the apartment.

It goes like this: Kazuko calls her mother’s cousin Izumi, with whom she is very close.

She asks Izumi to send her husband Shigeki to rent a flatbed truck and come help move some furniture.

Kazuko figures the boyfriend gets back around midnight.

She and Shigeki pack up the apartment — furniture, clothes, furs, jewelry, bankbooks, cash.

The sofa where the murder happens stays.

So does a shoe holder in the entrance hallway (remember that, it’s going to be important.)

They make it out before the boyfriend gets back — move the stuff to a nearby apartment.

Kazuko thanks Shigeki, who is none the wiser why the furniture is being moved at an hour’s notice in the dead of night, then heads back to meet husband Nobuo.

The kids are in bed by then. She and Nobuo drive into the mountains and bury the body in a forest.

A wicked crime has been committed, but Kazuko’s genius for improvisation is just beginning…

20 August 1982 (1 day after the murder)

The next morning, Fukuda bluffs her mother’s cousin Izumi — whose husband Shigeki helped move Asako’s furniture — into using the dead woman’s account details to withdraw ¥724,000 in cash from a local bank.

Kazuko immediately puts ¥650,000 of it into husband Nobuo’s bank account.

Second hubby Nobuo was a hard-working salaryman who didn’t earn much salary — and was supporting Kazuko, her two children from a previous marriage, plus their own two kids — in a house that was too large for them, that his younger brother had helped them buy.

Fukuda herself had ¥2m debt borrowed from 16 different consumer loan companies, used to support her own lifestyle — which she believed should be more glamorous and comfortable than Nobuo’s earnings could provide.

¥724,000 cash would help.

21 August 1982 (2 days after the murder)

Asako’s family informed the authorities of her disappearance, but the police did not immediately launch an investigation.

23 August 1982 (4 days after the murder)

Kazuko Fukuda is making love.

Not with hapless second husband Nobuo — with another dude, called Nakagawa.

They’re at a love hotel, paying by the hour.

And Kazuko is not Kazuko — she’s been banging Nakagawa for months under the name Hatsumi Takai.

Nakagawa is being transferred by his company to Kobe. “Hatsumi” pleads with him to take her along too, they can live together in bliss.

She doesn’t tell him her real name is Kazuko Fukuda, or that she’s married, or has four kids.

Or that she did murder four days prior.

Nakagawa had stood guarantor for an apartment for “Hatsumi” to move into.

It’s the apartment where she and Shigeki moved dead Asako’s furniture.

An apartment rented 12 days prior to the murder.

While Nakagawa and “Hatsumi” make love, Asako’s family are at a bank, pointing out the handwriting on the ¥724,000 withdrawal slip is not Asako’s.

The police are now interested.

They force their way into Asako’s apartment. It’s empty except for a sofa and a shoe holder in the entrance hall.

The cops find traces of blood on the sofa.

Plus a bank book for a ¥3m account hidden in the shoe holder — that Kazuko had overlooked when stripping the place.

So much for the theory Asako jumped town to escape her problems.

24 August 1982 (5 days after the murder)

Kazuko says goodbye to Nakagawa after their overnight assignation and leaves the love hotel for home.

She’s barely in the door and said hello to the kids when she gets a call from Izumi saying the police have called, trying to talk to Shigeki.

What happened is this: a neighbor of Asako’s found the midnight furniture move suspicious and noted the license plate of the flatbed truck Shigeki rented.

Kazuko calms Izumi. Puts down the phone and

RING RING

Another call.

Kazuko picks up. A stern male voice. Instantly she knows it’s the cops.

She does this: puts on a kiddie voice — pretends to be her own 3-year-old daughter.

“No, mommy’s not home. No, I don’t know when she’ll be home.”

She cuts the call.

Her overwhelming thought, for reasons that will soon become clear, is: I’d rather die than go to prison.

And then she sits down and has dinner with Nobuo and the 4 kids — husband and wife making small talk with their 13, 12, 5 and 3-year-olds knowing they spent the previous Thursday night dumping a body —

And after dinner Kazuko announces she has to go to Izumi’s house, and takes ¥150,000 household cash and one change of clothes, says a quick goodbye and leaves.

It’s the last time the family will ever be together.

Kazuko Fukuda is now on the run — and will be for the next 15 years.

And now we’ll leave her for a moment, to see how she came to be a murderer.

Just a Child

2 January 1948 (34 years before the murder)

Kazuko Fukuda was born in Matsuyama City to a single mother. She never knew her father, who left before she was born.

1949 (33 years before the murder)

Her parents divorce was confirmed when Kazuko was a year old.

1950 (32 years before the murder)

Her mother soon remarried, to fisherman from the tiny island of Kurushima.

The infant Kazuko lived with her maternal grandparents — she later claimed that had she stayed there her life would have turned out much differently.

1955 (27 years before the murder)

But when she was in the second year of elementary school, she joined her mother and new father on Kurushima, entrusted to the care of her step-grandparents, who treated her cruelly, amongst other things withholding meals.

1961 (21 years before the murder)

Kazuko moved or is moved to Imabari City, into the brothel her mother was running.

This, it won’t surprise you, was not an ideal nurturing environment.

Her father didn’t help by bringing random women home and beating Kazuko for kicks.

Kazuko becomes attention-seeking, validation-craving, uncontrollable, fucked up.

1964 (18 years before the murder)

Kazuko’s first love is a biker kid.

She’s found an anchor, he’s perfect, everything is perfect, everything is going to be okay.

Within months the biker drills his bike off a cliff and dies.

Kazuko drops out of school soon afterwards.

June 1965 (17 years before the murder)

Over her mother’s objections, Kazuko begins living with a new boyfriend.

She quits her virginity soon afterwards. They’re together in their own place — Kazuko is building her own family. It will be a family that does not replicate the mistakes of her own, the chaos and hurt.

Within three months, Kazuko committed her first major crime.

17 September 1965 (17 years before the murder)

Rain pounds the sidewalks.

Takamatsu City is being bullied by the 24th typhoon of the year, nicknamed “Trix”.

Two masked figures move like ghosts through the downpour.

One hops a garden wall, stops and helps the other up and over.

They move towards a traditional Japanese house, rain waterfalling from the eaves.

They try a bathroom window — it delivers — into the house they wriggle.

The head of the Takamatsu Regional Taxation Bureau wakes up to a knife up his nostril.

He can tell the masked bandits are a male-female duo.

Kazuko Fukuda and the Boyfriend disappear back into the screaming night with cash and fancy cameras.

February 1966 (16 years before the murder)

The kids had no life skills and spent money like water.

Five months after the robbery, they decide to cash the fancy cameras in at a pawn shop.

Bad idea.

One does not become head of the Takamatsu Regional Taxation Bureau without building juice with local law enforcement.

The word was out: look for the cameras.

Boyfriend quickly gets collared by the Ehime Prefectural Police.

He tells Kazuko the bad news: I have a record — theft — she had no idea, though she should’ve — guess what: I go to prison if I take another charge.

Here’s what we do: you take the rap. You have no record. You’re a woman. You’ll get a slap on the wrist and a quick release..

Are we, Kazuko, a team or are we not?

Time to show what you’ll do for the team.

12 March 1966 (16 years before the murder)

Kazuko Fukuda is arrested for the robbery.

Team-player boyfriend immediately reverse-ferrets and sets out a new position: she’s the ringleader. She came up with the plan. She thought the typhoon would be perfect cover.

Kazuko ends up in a legal jackpot.

She does not get a slap on the wrist.

She is not let go.

Kazuko instead finds herself victim of one of the filthiest scandals in Japanese legal history.

Quick break to say: if you’re reading this in your email account, you can comment on any edition of The Kyote by replying to the newsletter, just like a normal email.

And if you’re not reading us in your inbox, you might want to subscribe so you get your fix every Sunday at 19:00 Japan time.

Now let’s jump back into the story…

The Takamatsu Prison Outrage

1964 (18 years before the murder)

The “First Matsuyama Uprising” was a major shootout between Yakuza gangs that took place in Matsuyama City during 1964.

As a result, dozens of gangsters from the Gōda-kai gang were arrested and held in Matsuyama Prison.

Within months, a prison guard secretly delivered a letter to a Gōda-kai member he had previously known on the outside.

Bad idea.

Like any mafia, the Gōda-kai existed by finding weak people and squeezing them for money or favors.

Having turned out one guard, they began systematically targeting the rest of the officers.

1966 (16 years before the murder)

Within 18 months the Gōda-kai imposed a regime of their own: using keys to freely enter and exit the prison, as well as drinking, smoking and gambling.

And then they got the keys to the women's cellblock.

By this time the guards were thoroughly corrupted, and when the female prisoners started to be raped, they joined in.

Kazuko Fukuda was one of their victims.

Eventually, the Matsuyama Prison outrage became so known that it was even referred to the Legal Affairs Committee in the National Assembly.

However, the truth of the case was not revealed because two vice-wardens committed suicide — one hanged himself, the other leaped from the smokestack of an incinerator — and female prisoners who were victims of rape did not file complaints — it was later revealed — thanks to Kazuko Fukuda — that the Ministry of Justice had forced the victims to withdraw their complaints.

Even when the raped were revealed, the women had no legal recourse — because of the statute of limitations on sexual crimes.

Kazuko was transferred to Takamatsu Prison, only to be raped again by a prison trustee.

1967 (15 years before the murder)

Aged 19, Kazuko was released the next year, with one vow: she would rather die than return to prison.

She went to live with her mother, and understandably suffered a mental breakdown.

In desperation, her mother appealed to her cousin Izumi to let Kazuko move in with her. The two quickly became friends, and Kazuko find someone that she could confide in.

1969 (13 years before the murder)

Kazuko marries her first husband, and they quickly have two children together. To help the household finances, she began her first hostess job in Takamatsu’s Karawamachi 1-chōme nightlife district.

Mixing with the affluent customers, she understands her dream: a rich lifestyle with a stable family.

1971 (11 years before the murder)

Just two years later, at age 23, she opened her own “snack”, becoming a chii-mama, a young mama-san living off her ability to flatter her guests and manage the atmosphere of her own bar.

1975 (7 years before the murder)

But by four years later, Kazuko had divorced and remarried Nobuo, the jinxed second husband who would end up becoming unwilling accomplice after the fact in Asako’s murder.

And then the snack went bust.

1982 (the year of the murder)

At age 34, Kazuko is a financially struggling wife of four/sometimes hostess, drowning in personal debt, facing the fact that her dreams of an affluent lifestyle may have been torpedoed permanently…

DAY 1 ON THE RUN

24 August 1982 (5 days after the murder)

After Kazuko walked out of the family dinner, never to return, she went directly to the hideout apartment where she had moved Asako’s furniture.

Up in the elevator to the sixth floor.

Right turn out of the elevator, heading for Apartment 604.

And as she turned the corner she saw two detectives standing outside the door of #604.

Detective One sees her coming and pivots into her path.

“Where are you headed, Miss?”

Since the murder Kazuko has been operating on a new plane of existence. If they had the term in 1982, it would be flow state.

She has become queen of bullshit. She’s visiting in friend in, what is it? I think Apartment #610? I don’t remember the number, it’s around the next corner.

Detective One smiles, moves out of her path.

Kazuko levitates down the hallway, around the next corner then bombs down the fire escape 3 steps at a time.

What she knows is this: it’s time to get far out of town…

The story of Kazuko Fukuda’s long escape continues in next week’s edition.

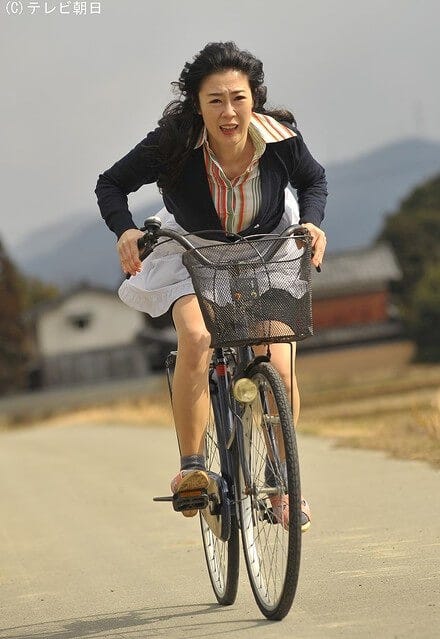

From next week’s edition: Bicycle Escape. Still from 2016 Fuji TV drama 『実録ドラマスペシャル 女の犯罪ミステリー 福田和子 整形逃亡15年』(“True Crime Drama Special: Woman’s Crime Mystery - Kazuko Fukuda’s 15 Year Plastic Surgery Escape”). Image: Fuji TV

Here’s a preview of the chapter titles from next week:

A New Face

The Candy Man/Bicycle Escape

Osaka Homeless Blues

Can’t Keep Her Down For Long

Rich Life

Never Take Your Murder Suspect On Public Transport

Trial

Final Exit

Thanks for reading — click the ♡ below if you liked this edition.

Until next time,

The Kyote

New? Sign Up Here

Feedback? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote is published in Kyoto, Japan, every Sunday at 19:00 JST