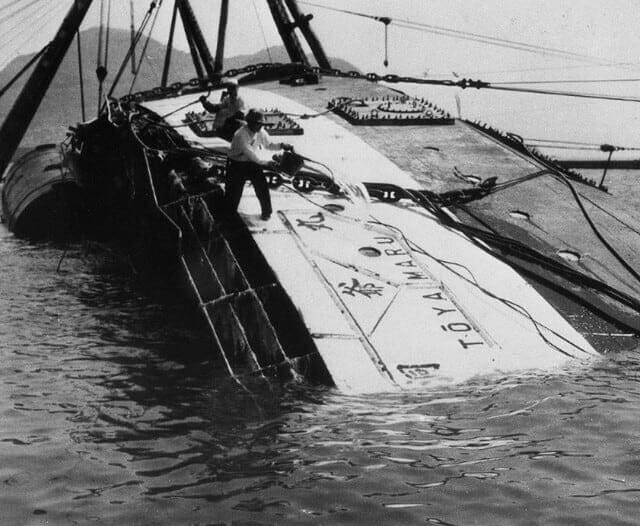

Tōya Maru. Source: https://blog.goo.ne.jp/goo3360_february/e/e59bab3a028ff4bea2f560d173d7b655

This week in 1954, five boats braved a typhoon between Japan’s main island of Honshu and the northern island of Hokkaido.

1,153 people died.

Today’s edition explains the story of Tōya Maru, Japan’s Titanic — plus the other 4 boats that went down with her.

We’ve also got your usual quiz, links etc.

Let’s dive into it:

THE QUIZ

A picture any Japanese person will recognize instantly — do you?

Question: what’s this?

Answer at the foot of the mail.

THE HISTORY

Japan’s Titanic

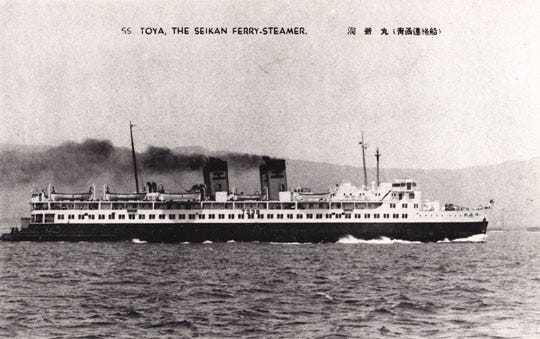

Tōya Maru, in better days. Image: Wikipedia

Typhoons hit Japan regularly.

They usually blast through the southern island of Kyushu, removing roofs and agéd relatives, but blow themselves out on the northern trek through Honshu.

Rare is the bastard that makes it all the way north to the Sea of Japan between Honshu and Hokkaido.

Typhoon Marie was one of those rare bastards.

September 26, 1954, Marie heads northeast with wind speeds of more than 100 km/h (62mph), predicted to reach the Tsugaru Strait in the late afternoon.

At 11:00, the train ferry Tōya Maru arrived at Hokkaido after its first crossing from Honshu.

Another ferry, the Dai 11 Seikan Maru, an old duffer of a boat, was supposed to do the return leg, but couldn’t be trusted on the rough seas.

So everyone, passengers plus train cars plus vehicles, jumped onto Tōya Maru instead.

Luckily, Tōya Maru’s captain didn’t like his chances either, and cancelled the crossing forthwith.

Unluckily, the weather cleared up — temporarily — and everyone assumed the typhoon had passed, as had been previously predicted.

Marie instead had merely paused to build up even more strength.

At 18:39, Tōya Maru departed with a full load of approximately 1,300 passengers — right into the eye of Marie.

At 19:01, Tōya Maru lowered its anchor near Hakodate Port to wait for the weather to clear up again. However, due to high winds, the anchor did not hold and Tōya Maru was cast adrift. Water entered the engine room, causing its steam engine to stop.

Tōya Maru was uncontrollable, at Marie’s mercy.

(4 other freighters dropped anchor too, around the same time, and were similarly screwed).

At 22:26, Tōya Maru hit bottom at Nanae Beach and a frantic SOS call was made. However, the waves were so strong it could no longer remain upright and, at around 22:43, Tōya Maru capsized and sank in several hundred meters off the shore of Hakodate.

Of the 1,309 on board, only 150 people survived, while 1,159 (1,041 passengers, 73 crew and 41 others) died.

Add the four freighters that sank at the same time and the total loss of life was approximately 1,430.12

* * *

So, whose fault was it? Some idiot captain taking his passengers for a spin in a typhoon?

Well: there was a technical enquiry (available online with an English executive summary). It contains a lot of charts and diagrams and other gubbins.

Basically:

The captains of all 5 boats did the right thing: dropped anchor bow to the wind.

All the ships had stern openings that allowed water aboard.

The 4 freighters were screwed by the volume of water they took on. Physics.

The volume of water Tōya Maru took on wasn’t fatal — but when it hit bottom, the loss of stability was too great to overcome.

The widow of Tōya Maru’s captain did the Japanese thing, and every day during rescue operations faced victims’ families and begged for forgiveness.

His body was found — in his gear, mid-captaining, trying to save his passengers.

There was still uproar, and a scapegoat to be found, and in the short-term the captain was the target.

Was it unfair for him to face post-mortem vitriol? Of course…but you’re the captain — and when it’s your responsibility, you might end up unfairly taking the blame.

Then again, that’s part of what you signed up for, if you don’t like it, remain a passenger.

* * *

The Losses

Japan, 1954, was not Japan now.

The efficiency, care, safety, and comprehensive records you’re used to did not exist then — so the official casualty figure of 1,153 is at best a guess, encompassing the chaos of unrecorded passengers, passengers with no birth records, and passengers who disappeared into the deep, unmissed and unmourned, their bodies never to be recovered.

The memorial of the disaster, near Nanehama Station in Hokkaido, has no names listed for the victims.3 (Another way to remind yourself how chaotic post-war Japan was are photos of the commuter trains, with people hanging out of their doors or onto the roofs like a picture straight out of India).

But there was one set of passengers who had their deaths decently recorded: a contingent of American forces who happened to be aboard Tōya Maru. Thanks to the valiant efforts of volunteers, we know who a number of them were.

Any rollcall of American forces reminds you of how much of a melting pot the country is: Gallos sit side-by-side with Gonsalves and Grahams, and Michalaks and Vaillancourts and Wendelschafers and Oteros — but at the link above we also catch a glimpse of individual tragedies, tiny in the context of the four-figure list of Tōya Maru victims, but each a small annihilation of a family. See:

Sergeant Willard Batchelder, wife Kazuko and three-year old child, Makié

or

Ada L.C. Willis, school teacher

or

Two unidentified soldiers accompanying a mail railway car

And then the somehow merciful:

Sergeant First Class Charles Champagne (his wife, Emiko, was also aboard, but survived).

(One wonders whatever happened to Emiko Champagne…)

Also: Dean Leeper, an American missionary, who drowned after giving his life jacket up to a Japanese kid.

His son Steven, age 6 at the time of his father’s passing, later came to Japan and became the first American to be appointed chairperson of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, which operates the Peace Memorial Museum.

* * *

The Movie

They made a movie of it. Actually, they didn’t. They should’ve made a movie of it, instead they made a movie adjunct to it:

Kiga Kaikyō (飢餓海峡), literally “Hunger Straits”, 1965, director Tomu Uchida.

Based on a novel by Tsutomu Mizukami.

Some doofus renamed it A Fugitive from the Past for English speakers.

Story: Our Guy is suspected of killing two accomplices by throwing them out of boat; their bodies wash up as Tōya Maru victims — but a cop smells a rat! 10 years later Our Guy has started a new life but can’t escape his past — murders a woman who recognizes him and runs. Cop pursues.

Uses the Tōya Maru disaster, in other words, as a cheap bit of background detail for the top of the movie.

This is a problem. Why? It doesn’t understand the difference between novels and movies. In a novel you can fart around with the Tōya Maru disaster as one note in a complex melody. Can’t do that in a movie, because:

In the same way when you heard about people who faked their death in 9/11 and thought “that’s a movie!”, you have to then realize that movies are about drama, and the locus of drama in 9/11 is 9/11, not someone faking their death in 9/11, and, in fact, making a movie about the latter is just exploiting the tragedy.

Future megawatt movie star Ken Takakura plays the cop.

183 minutes long!

The movie uses the Toei W106 Method© to achieve some moody cinematography. Translation: they filmed it in 16mm, blew it up to 35mm and let a madman loose in the developing room, so the film looks like trash — deliberately.

Kiga Kaikyō’s patented loss of picture quality. Thanks, Toei W106 Method!©

THE LANGUAGE

5 Japanese Words of Dutch Origin

During the Edo period, the Netherlands was one of the few countries allowed to trade with Japan. Rangaku — “Dutch learning” (蘭学) — introduced Western science, tech, and culture — and some of those words are still used in Japanese today:

1️⃣ Penki (ペンキ) - paint

From the Dutch word pek, which doesn’t mean paint. It means pitch or tar, so this is a Japan-only language evolution, the kind of which we love, but makes a certain type of person pull their hair out.

2️⃣ Koppu (コップ) - cup

Keen tripper-upper of English speakers, who ask the Japanese for a “cup” and get confused looks in return. Thanks to our Dutch brethren, drinking vessels are pronounced “kop”.

3️⃣ Otemba (お転婆) - tomboy

In Dutch, someone who is untameable is ontembaar — and in Japanese an otemba is a boisterous, bolshy girl. (NB: some dictionaries aren’t convinced the two are linked).

4️⃣ Pincet (ピンセット) - tweezers

Another confuser of English speakers, who wonder, puzzled, why a “pin set” is essential for doing makeup.

5️⃣ Gomu (ゴム) - rubber

From the Dutch gom, this one is used in exactly the same as in English — gomu talks about the rubber tires on your car, rubber balls, rubbery food, and — yep — condoms.

BONUS: the Tokyo district of Yaesu (八重洲), named after 17th century Dutch explorer Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn (it makes sense in Japanese, honest).

THE LINKS

3 things worth your time about Japan:

The Tree That Travels — on the late Michio Hoshino, nature photographer and essayist

Check out the first autumn foliage prediction map

THE ANSWER

Question: what’s this?

Answer: a saisenbako, the traditional donation box found at temples and shrines — now sometimes to be found with QR code or NFC for contactless payments (remember: the priests were Japan’s original marketeer money-makers)

Enjoy The Kyote this time? Check this out next: A Doomsday Cult Tried Rescuing a Lost Seal

We’ll see each other again next week,

The Kyote

Comment? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote is published in Kyoto, Japan every Sunday at 19:00 JST

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C5%8Dya_Maru

https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15441048

https://hoodcp.wordpress.com/2020/03/18/the-toya-maru-sinking/

You compared it to the Titanic but it reminded me of the movie Perfect Storm, which was also based on a true story.