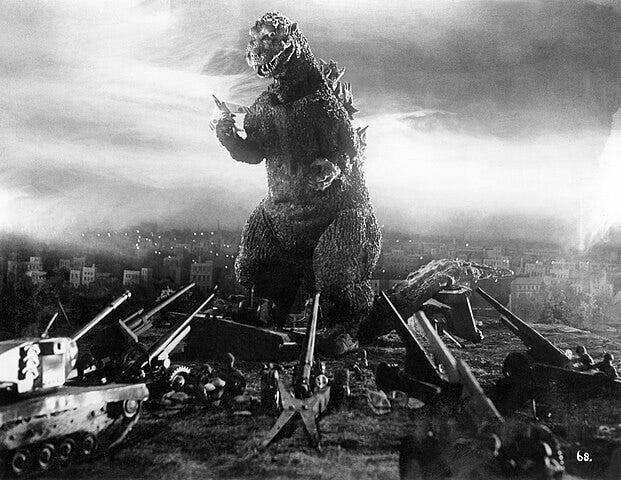

The Gruesome Deaths That Inspired Godzilla

Image: Toho Company Ltd/Public Domain

In port towns, it’s traditional to pray for the return of every fishing boat that sets out to sea. But this time, the fact the boat managed to return was the just the beginning of the nightmare.

* * *

Long-line tuna fishing has always been a tough racket.

On 22nd January 1954 the boys of the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (literally “Lucky Dragon No. 52”) chugged away from the port of Yaizu in Shizuoka Prefecture, heading for the tuna grounds of the South Pacific.

A mix of grizzled veterans of the oceans — plus World War II — and a half-dozen young men just coming of age, these were taciturn, hard-working guys who spent most of their lives doing the backbreaking work necessary to supply the mealtables of Japan.

Weeks later, beleaguered by crap weather and even crapper catches, the small boat ventured into the calm seas around the Marshall Islands. The captain knew one particular area had been declared off-limits, but the restricted zone was clearly marked on their maps, and they were well outside it.

Night, March 1st. Well into the second month of the voyage. Most of the crew are comatose in their births after another night of brutally tough labor. Fishing master Yoshio Masaki is one of the few people on deck, one man surrounded by hundreds of square miles of deep, oily darkness.

Suddenly the lights flick on.

Masaki, bewildered, throws a hand instinctively up to sunglass his eyes, and observes the western sky now sports an eerie orange sun.

In total silence this new sun expands to fill the horizon, creating a wavering heat-mirage that liquifies its edges.

Masaki watches, slack-jawed.

“What the hell is that?”

(says a voice somewhere behind him)

Masaki checks his watch. It can’t be dawn. It’s too early. It’s too fast. It’s too west.

Soon more of the boys are on deck, in their white fundoshi thong underwear and head-towels, checking out the lightshow.

Some of them are mesmerized. Some of them interested. Some scratch their balls and yawn.

It sure looks cool — but it gets old fast. One guy suggests an early breakfast and that’s when — 9 minutes after the light snapped suddenly on — the ROAR arrives.

The ROAR becomes BANG-BANG BANG-BANG BANG-BANG BANG-BANG, avalanches overlapping, an all-out sonic assault through which someone — a veteran— shouts “atomic bomb!”

Actually, it was much worse…

No more yawning now. Balls go unscratched. Masaki tells the boys: haul ‘em in and perhaps make it fast?

The crew bring in the lines, collecting their booty of fat Marshall Islands tuna, but eyes are constantly swerving to the horizon, where strangely layered circles of clouds are now slowly spreading from the direction of the explosion.

Then it starts to rain.

It wasn’t rain — it pelted them like rain — but it was white and it was ash.

It coated the ship and still-working crew with a gritty layer that stuck to their hands, necks, faces, hair and got in their mouths and eyes. It painted the dark blue tuna on the deck a ghostly grey. One of the still confused crew, Matashichi Oishi, even licked the ash out of curiosity.

The white rain lasted five hours — by which time the lines had been hauled in and some of the boys were already dizzy, puking, and spiking fevers.

Here’s what had happened: “Castle Bravo”. The U.S. military test of a thermonuclear bomb, which had turned out to be — whoops — more than twice as powerful as its designers predicted.

Lucky Dragon No. 5 was fully 86 miles from the test site, well outside the officially declared warning zone, but it turned out to be too close anyway.

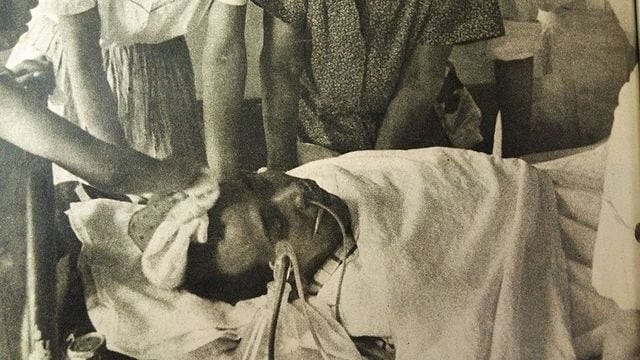

In what must have been at best a tense passage, it took two weeks for the boat to limp back to Yaizu, by which time most of the crew were suffering from headaches, bleeding gums, gruesome skin burns — plus their hair was falling out in clumps.

Sanjirō Masuda in the collective sickroom. Image: Mainichi Shinbun - 『日本写真全集 10 フォトジャーナリズム』小学館、1987年10月20日、ISBN 4-09-582010-1, Public Domain

It was soon front-page news The Yomiuri Shimbun splashed with “Japanese fishermen encounter Bikini A-bomb explosion test. 23 men suffer from A-bomb disease.”

Then the world caught on.

It was already known that high levels of radiation had caused what was then known as “atomic bomb disease” among survivors of the weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but that illness was associated with the radiation generated at the moment the bombs exploded.

Despite Japan's experience in treating nuclear radiation victims, the doctors treating the crew did not fully understand what they had experienced. Only after several tests were performed were did Japanese medical investigators find they were suffering from something else, “acute radiation disease”, that was caused not by the bomb but the radioactive rain it produced. The Japanese began calling this shi no hai, “death ash”.

You may have heard the term the international media came up with to describe shi no hai: fallout.

Yasushi Nishiwaki was one of the many Japanese scientists who immediately went down to see and try to help the victims. He had sent a letter to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (who shared responsibility for the tests with the military) to ask for steps to handle the victims, as well as a report on the nuclear tests conducted by the U.S..

However, the U.S. government showed its customary tact and diplomacy by stonewalling requests for information before grudgingly sending two doctors — who prevail upon the Japanese authorities to confine the now very bald fisherman to the hospital to be badgered with questions and all manner of medical tests.

The crew were also — in a gross slander — accused of being Russian spies who had entered the exclusion zone deliberately.1

Aikichi Kuboyama.

Six months after the Lucky Dragon returned to port, Aikichi Kuboyama, the ship’s radioman, died, never having left the isolation ward. Official cause? Liver failure. He’d had a dicky liver for years, true. But it was clear that radiation had weakened his immune system so much that that was what actually did him in.

The Asahi Shimbun asked “Has the death of a citizen ever been watched by so many eyes?” Probably not.

Cut to Edward Teller, one of the geniuses who developed the hydrogen bomb, whose reaction was the slightly less than compassionate “it’s unreasonable to make such a big deal over the death of a fisherman.”2

(Teller, it won’t surprise you to learn, was one of the inspirations for Dr. Strangelove)3

* * *

The ash rain was not the only fallout from the Lucky Dragon. The contaminated tuna the boat had landed was shown around the world — not the kind of PR that does a fishing industry much good.

Hoping to get ahead of the panic, Japanese health authorities ordered tests on any fish caught in a 2,500-kilometer radius around the bomb test site. Bad news: thousands of samples turned out to be radioactively contaminated and unsafe for human consumption.

If you want to, you can find the footage of pits being dug and thousands of tonnes of fish being poured in and buried.

“No atomic tuna sold here”. Notice outside a fishmonger in Yaizu. Image:『アサヒグラフ』 1954年3月31日号

Officials at the US Atomic Energy Commission, who, along with the U.S. military were responsible for the whole fiasco, tried to play down the risk, but food companies around the world shut down fish imports from Japan, devastating the entire industry — devastating the port towns like Yaizu from which fishermen had set sail on their dangerous voyages for centuries.

Three Films That Resulted

GODZILLA (1954)

Screenwriter Ishiro Honda was scribbling away at the script for dumb monster movie when news of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru broke, and — clever guy — immediately nicked some details to make his script more upmarket.

Within months Godzilla was in theaters: the crew of a fishing ship sees a strange underwater glow, recoils in terror from a blinding flash, and get vaporized leaving the charred hull of the empty ship bobbing in the waves.

Gojira’s this ancient monster stirred to life by an immense human-made explosion and, pissed off at his long sleep being disturbed, boots island villages to pieces on the way to attacking Tokyo with radioactive breath that sets anything on fire.

We end with the characters reflecting on the catastrophic power of nuclear weapons and the possibility that another Godzilla could emerge if humanity continues its reckless use of science.

Two years later they released a chopped up U.S. version, with Raymond Burr inserted as a radio journo witnessing the Tokyo smash-job and telling his audience “I’m saying a prayer, a prayer for the whole world.”

OPERATION IVY [Made: 1952, Released: 1954]

Two years before the Daigo Fukuryū Maru-irradiating Castle Bravo test, the U.S. military had made an hour-long documentary film for internal use named Operation Ivy, which focused on the 1952 test of a nuclear bomb nicknamed Mike.

When the film was screened for President Dwight Eisenhower, he was so shaken that he ordered that it remain permanently classified, afraid it would terrify the public if ever released.

However, within two weeks of the Lucky Dragon’s return to port, with the world now aware of the tests and pressuring the American government to open up, permission was hastily given for Operation Ivy to be distributed.

It’s a standard military PR slop for the almost the entire first hour — trying to lull the audience with impressive plant machinery! Impressively sweaty men prepping machines! Oooh, let’s take a cheeky seat in the admiral’s chair!

Finally they drop the damn bomb and it falls falls falls falls then BOOM! The terrifying destructive power of thermonuclear weapons, which the world had never seen before.

They let the shot run without narration for nearly two minutes.

As Eisenhower predicted, the film terrified a lot of people. Operation Ivy played repeatedly on US television stations, and within days was being shown around the world.

People already knew atomic bombs plus Cold War, but the film made them aware that thermonuclear weapons posed an existential threat to life on earth.4

第五福竜丸 [LUCKY DRAGON NO. 5] (1959)

They also did a drama, directed by Kaneto Shindo (whose The Naked Island, Onibaba and Kuroneko you already know, or should).

The movie — available in full on Youtube — perhaps understandably has too much explainy-explainy and not enough time spend with our boys, building. them as three-dimensional people we care about.

The opening, which should be sweethearts-and-mothers-tearily-saying-goodbye stuff, fueling us up with emotional rocket fuel for the whole picture, is hamstrung by lack of sound (some penny-pitching studio dork insisting they stick music over it to avoiding having to pay for the audio department perhaps?)

There’s some interesting business on the boat — which was obviously a bitch to film — and then Act I ends with the bomb going off. As you’d expect from Shindo there are some arresting moments here: the crew member getting bored of the lightshow saying "let's eat!" just before the soundwave belatedly hits, and the fallout is also brilliantly done, including some post-processing effects.

Then, instead of what could’ve been the thrilling option — a dicey voyage home where one by one the boys take sick and we wonder if they’ll ever make it back at all, — Shindo cuts us suddenly to the boat arriving back in port (then again, that’s how we wrote this article too, so who are we to argue).

Then it’s lots and lots and lots of talk (including one scene where the Americans deny knowledge of what happened, the dialogue all funnelled through an interpreter so we have to hear everything twice).

Act III is a funeral. It’s important. It’s not entertaining.

But the real highlight of the entire picture is the deeply human scene when the boys excitedly watch a report about their own story on a television especially brought into the hospital ward.

Postscript

How the boys fared in the years afterwards:5

After being released from the hospital, Matashichi Oishi left his hometown to open a dry cleaning business. Beginning in the 1980s, he frequently gave talks advocating nuclear disarmament. His first child was stillborn, which Oishi attributed to his exposure to radiation. In 1992, Oishi developed cirrhosis of the liver but recovered after successful surgery.

Misaki Susumu opened a tofu shop after the incident. He died of lung cancer in Shizuoka Prefecture at the age of 92.

Masayoshi Kawashima (川島正義), tried to earn a living making pouches after his release from the hospital, but it failed. Kawashima returned to fishing but died soon afterwards aged 47.

Sanjirō Masuda (増田三次郎) died aged 54 after a constant battle with ill health including cirrhosis of the liver, sepsis, stomach ulcers and diabetes.

Yūichi Masuda (増田祐一) died aged 55 after collapsing suddenly. Cirrhosis of the liver was cited as a cause.

Shinzō Suzuki (鈴木慎三) died on 18 June 1982, aged 57, on the Meishin Expressway after the truck he was driving was involved in a rear-end collision, and burned to death in the wreckage.

Hiroshi Kozuka (小塚博) was diagnosed with stomach cancer in March 1986. He underwent surgery and had two-thirds of his stomach removed.

In 1987, chief engineer Chūji Yamamoto (山本忠司) was admitted to a hospital and was diagnosed with liver, colon, and lung cancer. Oishi Matashichi visited Yamamoto in the hospital along with another crew member, Tsutsui (筒井). Yamamoto to succumbed to his cancer 13 days later on 6 March 1987, aged 60.

Kaneshige Takagi (高木兼重) died of liver cancer aged 66. His widow explained that an employee at the crematorium told her that the bones of her husband after cremation were the most thin and fragile that they'd ever seen.

Until next week,

The Kyote

New? Sign Up Here

Feedback? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote is published in Kyoto every Sunday at 19:00 JST

https://www.spokesmanbooks.com/Spokesman/PDF/Webb125.pdf

http://review31.co.uk/article/view/730/life-is-precious

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Strangelove#Dr._Strangelove

https://thebulletin.org/2018/02/how-the-unlucky-lucky-dragon-birthed-an-era-of-nuclear-fear/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daigo_Fukury%C5%AB_Maru#Health_history_of_the_surviving_crew

Absolutely horrific. Yet another great post from The Kyote! Thanks 🙏

Excellent description of that horrifying event. Indeed, 1954 was an important and problematic year for postwar Japan. You can find more info about the events preceding the release of Godzilla in my recent essay: https://giannisimone.substack.com/p/1954-the-year-of-the-beast