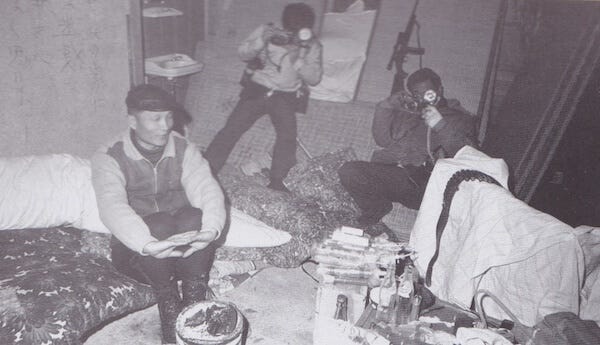

Kim Hyi-ro, mid-crime. Image source: Shinchosha

1. WANTED KILLER IN DEADLY STANDOFF — HOSTAGES AT RISK!

By your special correspondent on the scene at Sumatakyo Onsen, Fukushima Prefecture. Winter 1968.

Fujimiya Ryokan, a serene guesthouse nestled in the heart of this small hot spring town, has become a powder keg of fear in the past few days as murder suspect Kim Hyi-ro wages his explosive standoff against police in a scene straight out of a nightmare. The once-tranquil ryokan is now the site of a chaotic drama that has gripped the nation, with five innocent lives hanging in the balance.

Inside a cramped six-tatami room on the second floor, Kim has transformed the space into a macabre fortress of destruction. Rifle bullets spill across a tray like pills, while sticks of dynamite scatter the tatami mats, perilously close to the bare flame of a charcoal grill. The room's windows are barricaded with stacked futons and tatami mats, creating a claustrophobic lair bristling with menace.

Police Chief Keiji Takamatsu, top man on the scene, has vowed to prioritize hostage safety, yet the tension is as volatile as the dynamite Kim uses to threaten the nation. Armed with his rifle and a will of steel, Kim periodically shatters the relative calm by firing wildly or setting off dynamite with deafening booms. “I will air my grievances against the discrimination Koreans face in Japan!” he declares, as his demands—and his threats—escalate.

Yesterday Kim handed his “will” to a trembling reporter. "Show the world my story, and I’ll let them go," he growled. Miraculously, he has released some of his hostages, but not without ratcheting up his demands.

On the morning of the 23rd, Kim forced Chief Takamatsu and other officers to make a groveling television apology for their alleged derogatory remarks about Korean residents in Japan. But as the drama drags on, the public’s patience wears thin. “Why are the police allowing this maniac to hold us hostage as a nation?” critics demand. Pressure mounts on Takamatsu, who remains steadfast but visibly weary.

For now, Fujimiya Ryokan teeters on the brink of catastrophe. Inside the barricaded room, every second feels like an eternity, every sound a potential explosion. Outside, the nation holds its breath, praying for an end to the madness. Will this nightmare end in rescue—or ruin? Stay tuned as the drama unfolds.

2. Childhood

Kim Hyi-ro was bullied relentlessly.

Born in Japan in 1928 to Korean parents, his father passed away when he was three and his mother struggled to make a living selling pig’s feet. His mother soon remarried, but Kim did not get along with his stepfather. Growing up in extreme poverty and facing ethnic discrimination from his earliest years in elementary school, he dropped out, later running away from home at the age of thirteen, living on the streets and stealing food when he was hungry.

Later he explained “at that time, if you were Korean, you had no foundation for living in Japanese society. Many people committed suicide because they could not overcome the pain of discrimination. However, no matter how many times one of us died, they would never appear in the newspaper. They were just deaths for the dogs. When a serious crime occurred, they would fabricate evidence and frame a Korean living nearby. They would even sentence them to death unjustly.”1

Kim Hyi-ro was arrested in 1943 for a series of thefts and other crimes, and spent the rest of the war in a juvenile asylum. He was imprisoned again in 1946 for theft and embezzlement, divorcing his first wife the same year. For the next 20 years, he was in and out of prison, repeatedly committing crimes such as theft, fraud, and robbery.

3. Shooting gangsters

After a life of petty crime, at the age of fort Kim found himself struggling financially, surviving by borrowing money from loan sharks.

On February 20, 1968, Kim arranged to meet members of the Yanagawa-gumi yakuza gang at a club called Minx in the entertainment district of Shimizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture. He had promised to repay his debt to them. That did not happen.

Instead, he entered the club armed with a rifle and opened fire on two gang members, one of whom was a minor, killing both instantly.

Then Kim fled to Fukushima Prefecture, where his actions would soon make him infamous.

4. Hostage-Taking

Kim Hyi-ro, warming his hands on the charcoal brazier. Note sticks of dynamite. Kim’s rifle is propped behind the photographers. Image: Mainichi Shimbun

Kim took 18 hostages at the Fujimiya Ryokan.

If this had happened today, in the modern paramilitary hostage rescue team era, it would have been resolved within hours with a swift bullet to Kim’s head. But this was 1968, and instead the situation spiraled into a chaotic media spectacle.

Kim informed the police of his location and set out his demands: an apology for all the acts of discrimination he had faced as a Korean resident in Japan's legal system.

With no crowd-control measures in place, the inn quickly filled with reporters as well as the police, just as Kim had intended.

The police passively observed, unwilling to act out of fear that the hostages would be killed in front of the nation’s press; instead, Kim held press conferences, skillfully shaping the media narrative, while the two dead gangsters faded from memory.

The siege was broadcast live on TV and radio, with variety shows even placing live calls to the Fujimiya Inn to interview Kim, prioritizing ratings over the safety of the hostages and the wishes of their families.

The most shameful acts of the media were truly reprehensible, such as asking Kim to stage attention-grabbing stunts, like pointing his rifle in the air and firing it for the cameras. Kim complied with these requests, staging dramatic shots that were only later exposed as having been fabricated.

The incident also made front-page news in South Korea, where Kim was hailed as a 'national hero who fought against discrimination' — in a nation acutely sensitive to Japanese chauvinism in the wake of the various ruinous occupations of the Korean peninsula, which remained (and remain) a potent issue in the public consciousness.

5. Kim Gains Support

It wasn’t only the South Korean public that were expressing support for Kim.

A group of prominent intellectuals, including Michihiko Suzuki, Mineo Nakajima, Rokuro Hidaka, Yoshio Nakano, and Jukichi Uno, signed a petition in his defense.

Amid the madhouse situation, they, along with a group of lawyers, decided to head up to the siege and visit, bringing with them a tape recording of the petition:

“Kim began talking about his upbringing and how he turned to evil. [The intellectuals were] weeping as they listened. In front of them, a pot of sukiyaki bubbled on a charcoal grill. Meanwhile, Kim calmly held his hand over the fire, unfazed by the discomfort. It was a surreal scene.”2

(It remains a fact that individuals who try to bring attention to their causes in Japan through acts of extreme violence can achieve their goals — see Tetsuya Yamagami, who assassinated former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe out of resentment against the Unification Church (Moonies), whom he accused of destroying his family. Yamaguchi remains in prison awaiting trial, but the government has since heeded his demands to clamp down on the Church, seeking to strip it of its religious corporation status.)

* * *

The police, finally, got fed up with Kim’s grandstanding and decided to use his thirst for publicity to their advantage.

Nine cops were equipped with cameras, recording devices, and press kits, and infiltrated Kim's hideout in the guise of reporters.

While Kim was freeing a male hostage, the goon squad jumped on Kim and arrested him — in front of the gathered members of the actual press — and dragged him from the inn.

The hostage crisis, which had lasted for about 88 hours, finally came to an end.

6. Prison

Kim was charged with murder, unlawful confinement and violation of the Explosives Control Act.

During the trial the main point of contention was the influence of Kim’s upbringing as a Korean resident of Japan on his crimes. The prosecution sought the death penalty, arguing that Kim’s retroactive attempt to link his origins to the crimes did not excuse his guilt for murdering the two gangsters

The defense began with an audacious but failed effort to have the charges dismissed on the grounds that Kim had never been given the opportunity to choose his nationality and therefore could not be tried in a Japanese court.

In June 1972 , the Shizuoka District Court sentenced him to life imprisonment, rejecting the prosecution’s demand for the death penalty.

Kim had successfully highlighted the plight of Koreans in Japan, but was now going to do hard time for the two cold-blooded murders plus the 4-day hostage drama.

This could have been the end of the story. Instead, there remains Kim’s bizarre prison life, his release — despite the life sentence — to national acclaim — the movie — the musical — plus the other attempted murder/arson he committed at the age of 71…

* * *

“If there was any trouble, it would’ve been reported heavily. That’s why the wardens were careful not to be punished, and thanks to that, I was treated well. When I asked for tuna sashimi, they would make it for me once a month.”3

As soon as he was behind bars, Kim used his new celebrity to manipulate the prison system. Claiming that associates of the gangsters he killed might attack him, Kim secured a cell in a block reserved for female prisoners.

Then he really started the manipulation, threatening to commit suicide unless his escalating demands were met, knowing the criticism the prison authorities would receive — and soon he was being allowed to take walks and meet people freely, and bring in money or other valuables.

He was allowed to order food delivered from outside restaurants — when he didn’t feel like using his in-cell kitchen, complete with cooking knife. He also had three cameras, a telephoto lens, a tape recorder, a transistor radio, perfume and a goldfish bowl.4 Guards even provided him with adult photos.

Still, if we were imprisoned for life, we’d probably pull any lever we could to improve our conditions — but according to a book of prison guard reminiscences, things took a very dark turn, as he allegedly fed female prisoners restaurant food that he had laced with sleeping pills5 — what might have happened afterwards can be inferred.

(The prison guard who provided Kim with his kitchen knife committed suicide after the details became public; Kim’s own lawyer expressed disgust at his client’s callousness over the incident.)

7. Release / Hero / Another Attempted Murder

Commemorative photo taken when Kim Hyi-ro arrived in Korea. Source: Ladykhan

After serving 32 years in prison, Kim was released on parole on 7 September 1999 at the age of 70, on the condition that he leave Japan and never return.

He moved to South Korea, arriving with great fanfare (see photo above), and was given a luxury flat and living expenses.

However, having lived in Japan his entire life, he was unfamiliar with the language, lifestyle and values of Korea, and found the transition difficult.

Said Kim, in an interview years later: “At first, I had high expectations of coming to my home country, but I was also very disappointed. I think that in Korea, people are often judged by money.”6

He was targeted by financial scammers, one of whom was his own wife, a woman surnamed Don, who had befriended and married him in a prison wedding in 1979. She embezzled about 300 million won in donations and sponsorships from various circles that had been given to Kim to support him for a minimum of 10 years after his release.

Despite this, Kim unwisely forgave her — then woke up from a nap one day to find her missing, along all of his remaining assets. She was tracked down after being on the run for over a year and arrested for theft and forgery, but Kim made no attempt to sue for return of the money.

It wasn’t long afterwards an incident occurred that he was much less sanguine about, and saw his propensity for solving his problems with violence return.

Soon afterwards he met a married woman who, an elderly Kim later insisted, was just a friend, consoling him in the aftermath of his wife’s betrayal. However, “her husband started spreading strange rumors. He said that he would kill me if I saw him. So how could I stand it? I boldly went to see him and said “go ahead and kill me if you want.” He hit my face with a wooden club with nails in it, leaving a big wound on my jaw. The scar is still deep today.”7

The official court account is rather different: it seems Kim broke into the husband’s apartment, attacked him, then started a fire, trying to kill the husband and destroy the evidence.

He was arrested on suspicion of attempted murder and arson but, after being diagnosed as having a personality disorder, was sent to a sanitarium rather than prison. As a result, a Korean musical about his life that had already scheduled an international tour was abruptly cancelled, just before its premiere.

He was released from custody two years later.

8. Postscript

As a result of the privileges Kim was given in prison (which, as noted above, may have included f freedom to abuse female prisoners) the Director-General of the Ministry of Justice's Corrections Bureau and 13 senior legal officials were disciplined.

Kim’s War (金の戦争), a Korean movie about the incident that portrayed Kim in a heroic light, was released in 1992.

In later years, living an isolated life in Busan and suffering from ill health, Kim tried to get permission from the Japanese government to visit Tokyo for medical care he could not afford in Korea. He was turned down.

In March 2010, citing a wish to visit his mother’s grave, Kim planned another petition to the Japanese Ministry of Justice for permission to enter the country. However, he died of prostate cancer at a hospital in Busan on March 26, 2010, at the age of 81.

He wished to be buried at his mother's gravesite in Shizuoka Prefecture, but due to discord with his remaining family, including a younger brother who became a professor at Tokyo’s prestigious Meiji University, instead his ashes were scattered at sea — although a dead link can be found to a news story whose headline implies some portion of his ashes may have been scattered at the scene of the hostage incident.8

The Kim Hyi-ro incident prompted the Japanese police to establish their first ever sniper units. The first time such a unit was deployed was in the Setouchi Hijacking Incident that occurred on May 12, 1970, about two years and three months later. A member of the Osaka Prefectural Police sniper unit shot and killed the hijacker of a ship live on television — opening a new era, where law enforcement was no longer afraid to intervene despite the presence of reporters.

The 88 hours that Kim Hyi-ro incident lasted was the longest hostage situation in Japanese history at the time, but was surpassed four years later by the Asama-Sanso crisis in 1972, which lasted almost nine days.

Until next week,

The Kyote

New? Sign Up Here

Feedback? Just Hit Reply

The Kyote is published in Kyoto every Sunday at 19:00 JST

https://lady.khan.co.kr/issue/article/12310/?pt=nv

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%87%91%E5%AC%89%E8%80%81%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6#%E6%96%87%E5%8C%96%E4%BA%BA%E3%81%AE%E5%8F%8D%E5%BF%9C

https://lady.khan.co.kr/issue/article/12310/?pt=nv

ドキュメント戦後の日本: 新聞ニュースに見る社会史大事典 第 20 巻p87-90,1994年

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%87%91%E5%AC%89%E8%80%81%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6#%E5%88%91%E5%8B%99%E6%89%80%E3%81%A7%E3%81%AE%E7%89%B9%E5%88%A5%E5%BE%85%E9%81%87 cites https://www.amazon.co.jp/%E5%AE%8C%E5%85%A8%E5%9B%B3%E8%A7%A3-%E5%AE%9F%E9%8C%B2%EF%BC%81%E5%88%91%E5%8B%99%E6%89%80%E3%81%AE%E4%B8%AD-%E4%BA%8C%E8%A6%8B%E6%96%87%E5%BA%AB%E2%80%95%E4%BA%8C%E8%A6%8BWAi-WAi%E6%96%87%E5%BA%AB-%E5%9D%82%E6%9C%AC-ebook/dp/B007RL7RJM P74. The quote is “金の手料理や店屋物を出前させて会食し、男女の営みまで可能な状態だった。いい女が入所すると睡眠薬を混入した店屋物を食べさせ、レイプまでしており、やりたい放題であった”

https://lady.khan.co.kr/issue/article/12310/?pt=nv

ibid.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%87%91%E5%AC%89%E8%80%81%E4%BA%8B%E4%BB%B6#cite_note-18

Where the hell do you find these stories?!

Thank you for shedding light on this unusual episode in Japan's modern history. It's interesting that we take police snipers and the practice of keeping the press away from live crimes for granted today, when that wasn't always the case.